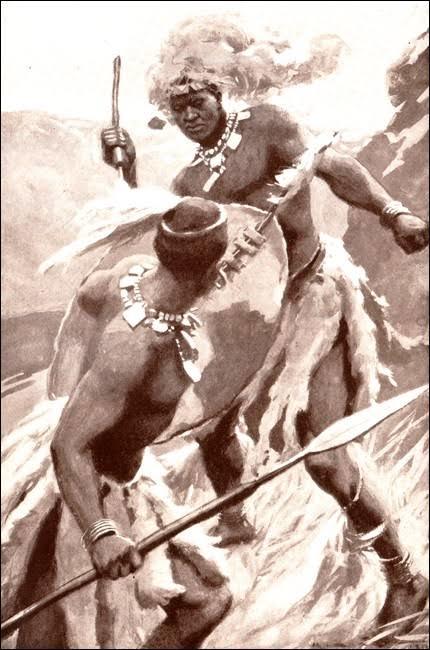

African Nguni or Intonga stick fighting paints an impressive image. Men dance around each other, kicking up dust, a stick in each hand. They tap one against the other, creating rhythm and music. They swirl their thin long wooden weapons round with dexterous fingers.

In a flash, they lunge towards each other with fierce, hard-hitting strikes. The rapid “tack-tack-tack” of parried attacks and whipping-sound of body-blows counter-point against the crowd’s cheer and whistle. African stick fighting, also called intonga or Nguni stick fighting in South Africa, have been a part of therural tradition for centuries. Today, you are just as likely to find you urban men in Cape Town practicing a version of this martial arts as they prepare for a weekend tournament.

A Time Honored Martial Art

At traditional ceremonies occurring in the urban centers of the country, the ritualistic display of traditional stick fighting is part pageantry and part heritage.

As a martial art, stick fighting is taught to young boys in rural communities on the coast and in the countryside. The boys from 9-years-old learn to spar as a rite of passage and proof of masculinity as they grow older. Xhosa rules of stick fighting dictate each combatant carries two sticks, both roughly 4ft long: One stick serves as defense, bound to the hand by a cloth or blanket wrapped around the knuckles for protection. The Zulu style of fighting includes a small animal-hide shield, called an izoliHauw, mounted on the defensive stick.

The other stick is for offense, usually aimed with intensity at the head, knees, wrists, or ankles. Strikes to the groin or ears are out of bounds and bouts last about 15 minutes or until the first serious blow is struck. As is traditionally practiced, it is a high-energy and often violent sport that is known to draw blood.

Traditional Stick Fighting as a Modern Combat Art

In the last ten years, the Nguni stick fighting tradition has experienced a grassroots revival as a recreational and competitive martial art in and around the South African city of Cape Town.

In 2010, Vuyisile Dyolatana founded the Qula Kwedini Stick Fighting Federation (QKSFF) that functions in the impoverished townships around the city of Cape Town.

In 2011, Jacques Sibomana created the Ultimate Stick Fighting Championships (USFC), leaning on the popularizing conventions and practices of Mixed Martial Arts tournaments. One goal of these organizations includes hosting monthly league competitions in the Western Cape Province, with cash-prizes incentivizing professionalization of the art. Because of the tournaments, local clubs sprang up around Cape Town and the use of social media promotion allowed stick fighting to enter the techno-cultural area.

Stick fighting is experiencing legitimization as a possible professional athletic pursuit, benefiting by the adopting of competitive martial art conventions. “In the past, they used to play raw,” said Vuyisile in an interview with Fighting Arts Health Lab, “but I discovered that it would be too dangerous.” Stick fighting as traditionally practiced often leave fighters walking away with ugly gashes and bloodied faces.

Consequently, Vuyisile started using bicycle helmets as protective gear, and later upgraded to skateboard helmets custom fit with grilled visors taken off cricket helmets. Other practitioners adopted different forms of protective protection, in some cases manufacturing synthetic fiber sticks to turn traditional stick-fighting into a safe and practicable sport.

Tradition Broke With The Inclusion Of Women

Part of Jacques Sibomana’s practice let young girls participate in training, diverting from stick fighting’s original patriarchal cultural setting. This expansion speaks to the heart of stick fighting as a martial art: this practice offers much more than a rite of passage for men.

From its rural setting, stick fighting is considered a way to learn virtues associated with martial art worldwide: discipline, hard work, perseverance, and how to handle confrontation and accept defeat.

This is part of why Vuyisile sees the practice’s promotion and growth in urban and township communities as particularly important.

As he stated in an interview with The Guardian in the young days of his organization: “In the rural areas intonga fulfills important social and cultural functions.

It teaches discipline and focus. I wish all South African, southern African and African cultures would revive stick fighting”.

For Vuyisile, stick-fighting can help uplift unemployed youth, diverting them away from street violence, drugs, and other social problems. “My main interest is innovation” he says, “To change the lives of the unemployed men so that they can benefit from the sport and make a profession out of it and earn a living.”

Strengthening National Pride

In addition to social development, an urban revival of traditional martial arts is a way to re-enliven and reaffirm national heritage, especially as South Africa is a country marred by a history of cultural repression under erstwhile apartheid law.

However, many of the initiatives and organizations that sprung up following the founding of the QKSFF and USFC have struggled to sustain themselves, with the USFC itself stopping its efforts in 2016. Today, in the Western Cape, it is Vuyisile Dyolatana who carries on the bastion of Nguni stick fighting as a recreational and competitive martial art.

While Vuyisile does not teach at the Warrior Training Centre often these days, he is currently developing a full curriculum and formalized convention for stick fighting. “I’m working out the curriculum now,” he says, “I have rules of engagement, point-scoring, protection gear.”

He wants to divide the curriculum into a year-by-year system, specifically set to accommodate the lifestyles of those from impoverished townships.

“From January, we will gather in Wynberg for training sessions,” says Vuyisile, the central area from which people from the surrounding townships such of Kayalitsha, Llanga, Muizenberg, and Fishhoek can come and participate. But funding remains a big obstacle for growth.

“It’s not easy,” Vuyisile sighed before continuing to recount his big plans.

Currently, Vuyisile is preparing his organization for the 2019 season and looking for additional funding to take Nguni stick fighting to the next level. You can find out more about, follow, and get in contact with the Qula Kwedini Stick Fighting Federation on their Facebook page. The title image is sourced from Arasa Malik.