Despite the prevalent traces of Judo in modern martial arts action choreography, it remains sorely neglected as either a subject or primary martial art across the whole of cinema.

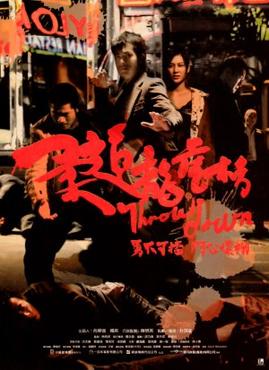

Johnnie To’s Throw Down (2004), a spirited tribute to master filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, was a long-awaited solution to the problem of how to put Judo front and center, bringing it off the tatami and into the streets.

The reality is that Akira Kurosawa solved this problem back in 1943 with his debut film Sanshiro Sugata, about the birth and growth of Judo through its first generation of students.

Johnnie To’s dedication of Throw Down to Kurosawa is also a statement that between 1943 and 2004, there is little to speak of in terms of cinematic Judo. Even in the subsequent 17 years since Throw Down, the fourth most popular martial art in the world has yet to be further embraced in widescreen format.

Make it Personal

Though in his 60’s, Master Cheng emerges from retirement to compete once again and is poised for a major match in hopes of bringing attention and students to the school. Sze-To seems to be trying not only to save his own ass but to strike it big enough to float the family school with a streak of fruitless gambling.

He is a former Judo prodigy who left the competition and severed ties with that world for unknown reasons, much to the consternation of his cohort. The legacy of his ascendancy in the sport remains a painful reminder of the loss that he drinks away.

Along comes Tony (Aaron Kwok), a saxophone wielding drifter who wears his inner child on his sleeve and who challenges every person he meets to a Judo match to feed some insatiable desire to test his mettle. He offers reasons, but the truth is that he simply lives and breathes Judo, and no gym can contain him.

Tony sniffs out Sze-To’s locale and starts pressing for a duel. Hot on the heels of Tony’s arrival is Mona (Cherrie Ying), a suddenly homeless aspiring pop singer with mediocre talent matched with an unassailable will.

Without a toe, let alone a foot in the door of the industry, and the clock ticking on her youth, she answers the open call for a Karaoke performer at Sze-To’s club, striking a contract with the inebriated manager.

Converging at the club on the same fateful night, Sze-To brings Tony and Mona into his bumbling schemes to acquire a seemingly astronomical fee via theft and gambling. Tony wants a match with the (formerly) best of the best, Mona wants a stage to reach for the stars, and Sze-To wants accomplices.

The symbiosis of this trio forms the curious beating heart of Throw Down, a film abundant with playful, sweeping, and dramatic moments, with coolness to spare.

Practically speaking, the most likely reason we don’t find Judo applied purely or straightforwardly in martial arts action cinema is because it isn’t explicitly lethal. Judo, a nearly 140-year-old Japanese sport which evolved out of Jiu Jitsu, eschews striking and kicking for a blend of throwing, pinning, grappling, and submission through joint locks and chokeholds.

Absent any strict adherence to the rules and forms of a school or style; any Martial Art Form somewhat ceases to be itself in modern blended choreography; thus, we find Judo moves but not Judo itself depicted on the screen. The same can be said of almost any martial art cherry-picked of its specific elements and effects, but Judo is rarer because it has so few filmic expressions.

The answer to bringing Judo to the screen is quite simple; everyone has to agree to follow the rules. This makes it necessary for the characters to know the rules, and thus we still need to skirt the competitive world of Judo. Proximity to that world is only as limiting as one allows it to be, and To does a magnificent job of keeping it to the absolute outskirts of the narrative, such that the only sanctioned match of the whole film takes place off-camera.

Every other contest happens in the streets, the club, in nocturnal neon or broad daylight. Throw Down couches its use of Judo among former practitioners of the sport, each grasping at a sense of nostalgia is found in that particular family of techniques. Everyone, even the gangsters and extortionists, essentially “follows the rules” when it comes to facing off because they are loyal to the form.

Time and Space

Johnnie To’s visual treatment of Judo makes a perfect case for its cinematic appeal and signals its visual potential as being equal to that of Boxing. The perpetual motion of the sport, its play of momentum and counterbalance, the rustle and drape of brightly colored Gi, the aggressive intimacy of opponents holding each other by the scruff of their uniform, the fluid unfolding of one technique into another, the contortion of bodies angling for an advantage, the swift and elegant sweep of legs… all these elements combine into a kinetic and kaleidoscopic image with so much visual possibility.

More exciting still is the unpredictability of the sport. Even within the span of a takedown, the opponent who will come out on top remains in question until the bodies hit the mat. Within the milliseconds of a fall, or at the tipping point of a throw, there is sometimes the potential to redirect ones fortune.

Indeed Judo is primarily founded on that principle of redirection. When an entire match is only 4 minutes, the drama of Judo is found in these fleeting, unpredictable arcs. In short, don’t blink. You will miss something.

Johnnie To’s slow-motion treatment of certain sequences brings out the physics of the martial art, as well as its irregular undulations of speed. His camera also moves in such a way as to bring the dimensionality of the sport to life as well, able to press in and out of spaces. Particularly memorable is the nocturnal, theatrically lit brawl that moves from the club to the streets. It makes for pure visual poetry to see Judo en masse on concrete.

A silent master cuts through the melee of churning bodies and takes down every opponent with a single crippling technique, shifting the energy of the scene between the elegant pageantry of bodies flipping in alternating neon and shadow and the cringe worthy punctuation of the masters effortless arm dislocations.

Genre be damned

Is Throw Down a Martial Arts film? An action Film? A drama? A comedy? Dare one say, a sports film? Easily one could say it is all of the above, but even that feels limiting. There is too much dynamism, too many free-wheeling artistic choices, too many perplexingly heartwarming moments, and too generous a spirit of visual play for Throw Down to be pinned as any type of true brawler.

Yet, Judo is the constant pulse of this gem of a film whose greatest appeal may simply be its brilliance as the fleeting story of a found family. Indeed that, combined with To’s recognizable flair for color and choreography, is what makes Throw Down so compulsively watchable, even 17 years later. How Judo hasn’t graced the silver screen in any significant way since has us at a loss.

Throw Down, recently restored in 4K by UK label Eureka!, is available on Amazon Prime with a Hi-Yah subscription.

Images source: China Star Entertainment Group