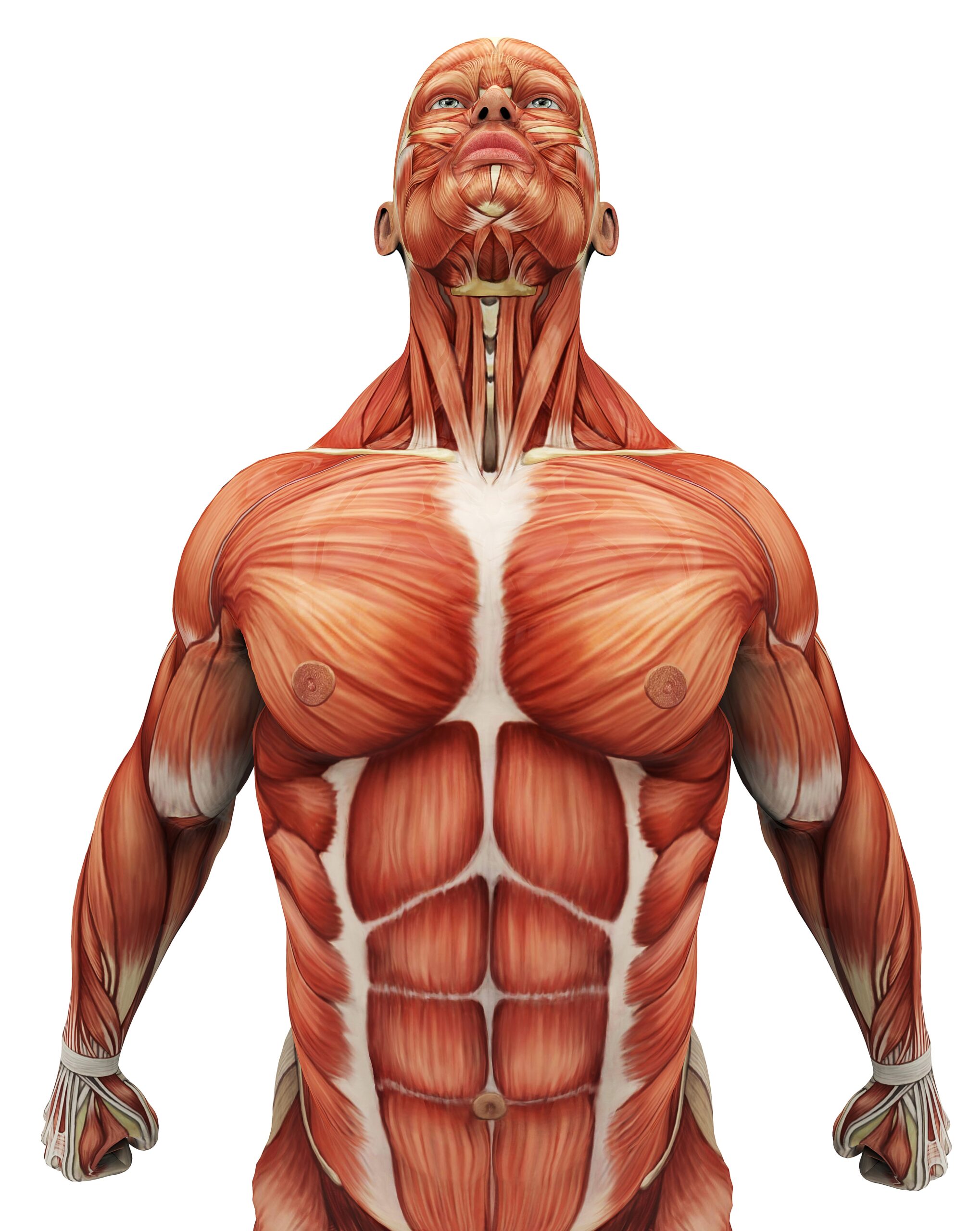

Combat Arts Chest Injuries Overview

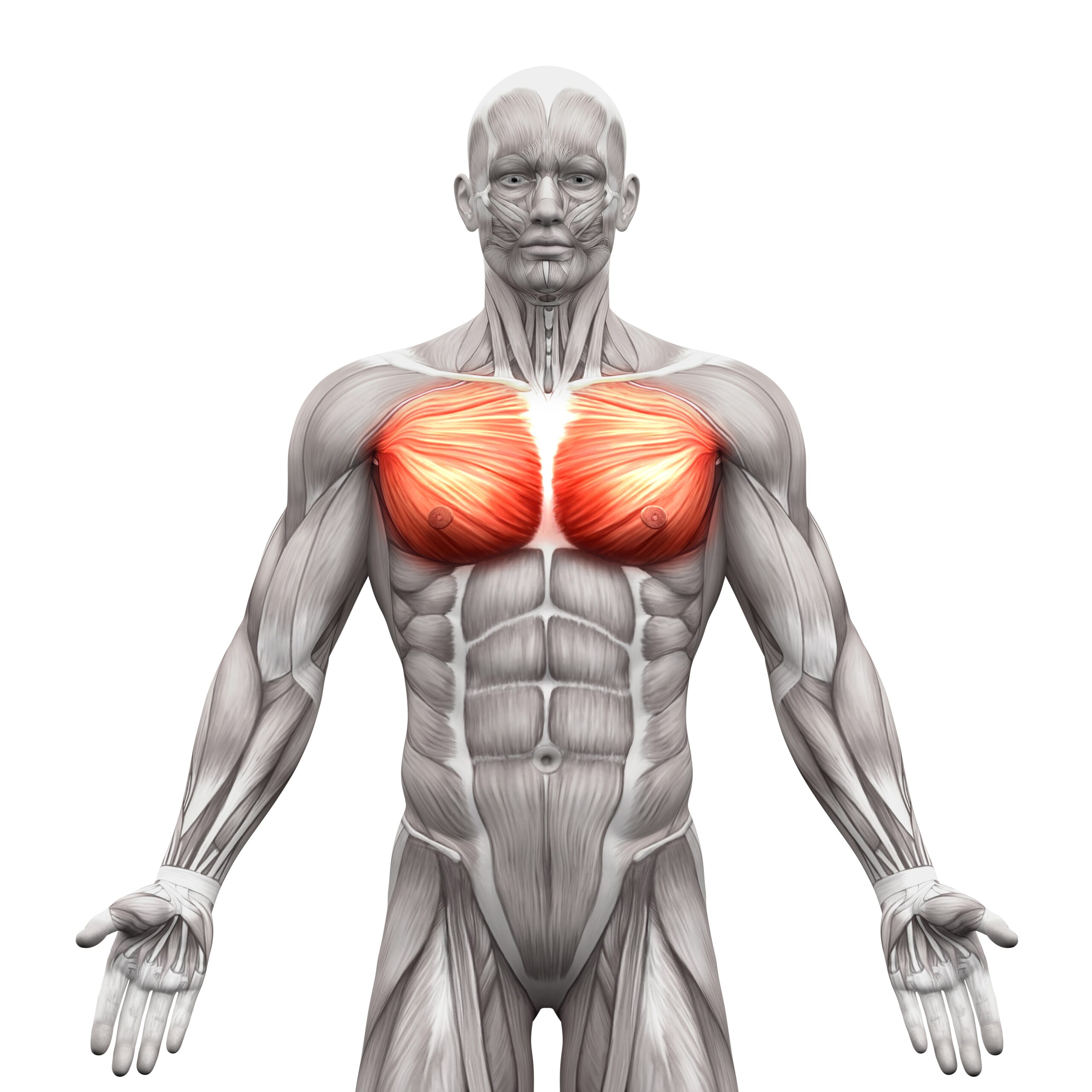

The chest area is particularly vulnerable due to the soft tissues and organs in the thorax. These include the heart, the lungs, the esophagus, the diaphragm, larger arteries like the aorta and veins.

Take Charles Oliveira who was taken out of his UFC match because he tore his esophagus. During a takedown, he twisted himself against the cage and that motion was enough to tear his esophagus. He had to pull out from the fight and taken to a hospital where it was found he had a microtear.

Causes of Chest Injury

Blunt force trauma through a high-velocity punch, kick, or jab can jar the chest. While the ribs do protect the structures beneath it, fractured ribs can also puncture the structures they are designed to protect. It is usually non-intentional trauma.

Trauma to the chest does come with the highest mortality; in some studies, up to 60%. Sudden violent tackles and moves where a sparring partner is on top of you, can cause blunt trauma. Chest to chest sweeps and other moves tend to exert a lot of stress on the overlying ribs causing them to develop stress fractures. The rib fractures can also cause penetrating trauma to the soft tissues and organs below.

Symptoms of a Chest Injury

Types of Chest Injuries

Since there are many organs, the injuries within the chest can be diverse. They could also be due to blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma. They include Sternal Fractures, Pulmonary injuries like pneumothorax and hemothorax, Cardiac injuries like hemopericardium or arrest, and injury to other structures like diaphragmatic injuries and an esophageal tear.

A High-Velocity Punch, Kick, or Jab Can Damage the Chest

Bounce Back Faster by Learning Injury Management Techniques

Related Injuries

A powerful 45⁰ blow could the sternum and its attached rib forcing it into the underlying structures. These could be chip fractures but require a lot of force to displace this bone. An example of how much force it requires can be found in Roman Polak. He went flying into a board and didn’t get up. It was a scary injury because right beneath the sternum lies the heart. Any injury to the sternum could spell disaster for the underlying myocardium.

Symptoms

Causes

Any sudden violent blow or kick to the sternal area can cause a sternal fracture. It takes a lot of force to damage the sternum. A sudden deceleration against the cage or a board can also cause the sternum to break. The injury could be more complicated if the associated rib breaks as well.

To learn how Sternal Fractures is diagnosed Click Here

Paul Felder was barely able to stand upright in his UFC fight when a hard kick landed in his chest. He assumed he had a fractured rib or a torn cartilage and even went on to do interviews after he was declared the winner. Except, he found he was getting progressively short of breath. While he was walking out to a post-match conference, the doctor stopped him and directed him to go to the hospital. He had a pneumothorax and any delay could have been fatal.

Symptoms

Causes

A traumatic pneumothorax or a tension pneumothorax occurs due to rib fractures, penetrating, and blunt chest trauma. Usually, the pressure in the pleural space is negative. When the chest wall expands outwards, the lung also expands outwards. The lungs collapse due to elastic recoil. If a tear or a rupture occurs in the pleura, communication between the alveoli and the pleural space opens up. Air fills this space and changes the gradient. The lung collapses until there is equilibrium between these gradients or the rupture is sealed. The pneumothorax or air in the pleural space enlarges, and the lung gets smaller. If this air pocket gets too large, then it compresses on the lungs and its ability to expand. Sudden, violent moves or a fractured rib can easily penetrate the pleural space. Fighters with primary lung conditions are at greater risk for pneumothorax. Alternatively, a hemothorax can also develop following blunt chest trauma, where blood pools in the pleural space.

To learn how Pulmonary Injuries is diagnosed Click Here

Cardiac injuries like myocardial contusions, hemopericardium, and cardiac arrests are rare in MMA. They do occur if the sternum or ribs are fractured or due to blunt abdominal trauma. The explosive forces cause the pericardial sac to rupture or damage the vessels, starving the heart of blood supply. In some cases, pooling blood in the pericardial sac can squeeze the heart and force it to do more work. Most fighters experience myocardial contusions but rarely all the fighting and dehydration can seize up the kidneys and gradually shut down the heart. Dhafir Harris known as Dada 5000 collapsed in the ring after he suffered cardiac arrest. He was severely dehydrated, renal failure was the thing that hit him. He didn’t know as he was taking punch after punch, that his organs were shutting down.

High-Velocity kicks and punches can directly impact the chest or compress the chest through sudden deceleration. A combination of the two can also cause cardiac trauma. Six mechanisms are suggested: direct, indirect, bidirectional, deceleration, blast, crush, concussive, or combined. These are usually unintentional in MMA as chest moves are illegal. The direct impact is the most common mechanism. Cardiac injury takes place when the ventricles are maximally relaxed at the end of the diastole. Bidirectional forces compress the heart between the spine and sternum. Deceleration mechanisms allow the heart to move freely. They cause valve ruptures, myocardial lacerations, and coronary artery tears.

To learn how Cardiac injuries are diagnosed Click Here

Diaphragmatic injuries are rare. The diaphragm can rupture when the intra-abdominal pressure suddenly rises over its tensile strength. It's important to understand that sudden deceleration, falls, and crush injuries can cause blunt trauma to the diaphragm. The diaphragm shot or punch to the celiac plexus that sits under the sternum is used to take out the diaphragm. The shot is powerful enough to have a fighter double over.

Blunt trauma is often the cause of diaphragmatic injury. It produces larger tears that measure 5 to 15 cm. often, they occur on the left side since there is a congenital area of weakness. Also, the liver on the right dampens any compression, thus making the left side more vulnerable. They rarely occur alone and simultaneous injuries of the abdomen, like splenic rupture and liver lacerations, may occur. Shots and punches aimed specifically at the diaphragm can cause it to tear.

To learn how Diaphragmatic injuries are diagnosed Click Here

Traumatic injuries of the esophagus are due to penetrating or blunt forces. Blunt injuries are masked by severe injuries like cardiac contusion or aortic dissection. Esophageal tears may not be at the top of the radar when it comes to MMA injuries in the chest. For Charles Oliveira, he stopped moving as soon as he was hit. His first complaint was, “I can’t feel my body” and the fight doctor suspected a spinal injury. Oliveira grabbed his neck and the fight was stopped. A CT caught the esophageal tear and the finding was incidental.

External trauma can damage the cervical and thoracic esophagus as they are located superficially. The esophagus is located near vital structures and does not have a thick serosal layer to protect it. Repetitive injury to the neck during training can damage neck muscles or ligaments. This puts fighters at further risk of further soft tissue injuries. The classic esophageal injury is the Mallory-Weiss tear. This occurs in people who drink alcohol and vomit so much they partially rip the esophagus. It tears the esophagus away from the stomach. The Mallory-Weiss tear occurs through the second layer but spares the tough outer muscular layer. The second and graver esophageal emergency is Borhaaves syndrome. Here, the esophagus tears through the muscular layer. The tear allows gastric contents to leak into the mediastinum, heart, lungs, and chest wall.

To learn how Esophageal tears are diagnosed Click Here

Common Injuries

Learn more about common chest injuries, visit our Common Injuries section.

Chest Injury Diagnosis

Chest injuries require tests that evaluate the lungs, the heart, the bones, the diaphragm, and the esophagus. The tests are varied because many systems have to be assessed and examined. They not only include radiology and blood tests, but cardiac monitoring and spirometry as well. Many of these tissues like the myocardium have a limited time to heal. With a window of 6 hours, tissues start to necrose without blood supply and the injuries to the heart and lung could be life-threatening. Hence, rapid diagnosis and treatment are necessary.

Injury Specific Diagnosis

Physical Exam

On physical exam, pain in the anterior chest wall pain is characteristic. Any evidence of shortness of breath like flaring of nostrils, use of accessory respiratory muscles, and increased respiratory rate point to respiratory distress. The doctor will ask the fighter to breathe deep and cough, both of which may aggravate pain.

They will check for point tenderness over the sternum. Associated soft tissue swelling, ecchymoses, or palpable deformity is diagnostic. On palpation, there may be fracture-related crepitus.

The respiratory, cardiac, and abdominal systems are thoroughly examined to check for rib fractures, flail chest, pneumothorax, hemothorax, cardiac tamponade, myocardial contusion, pulmonary contusion, and intra-abdominal injuries.

Imaging

The first test is the chest radiographs. It’s always done with the anteroposterior radiograph better for detecting sternal fractures. A lateral radiographic view is typically diagnostic. This is because most sternal fractures are transverse and any displacement in the sagittal plane is picked up easily on a lateral X-ray.

CT of the chest is commonly done in sternal fracture. Axial CT scans May miss transverse sternal fractures. A spiral CT scan is more sensitive. CT scan also provides an assessment of other organs in the chest.

Ultrasonography can detect sternal fractures better than plain radiography. Bedside ultrasonography reduces the diagnostic time, however, it largely depends on the skill of the technician. Echocardiography is done to detect myocardial contusions and view any wall motion abnormalities.

Lab Tests

Blood tests typically include the complete blood count and the basic metabolic panel. ABG is ordered to check the ph of the blood. Cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry are obtained in the trauma bay. Electrocardiograms are done to assess myocardial contusions. Enzyme markers of cardiac injury like Troponin are ordered. They are highly specific for myocardial injury.

To learn how Sternal Fractures is treated Click Here

Physical Exam

A very thorough pulmonary and cardiac examination is performed. On examination, the doctor will find, signs of respiratory discomfort, increased respiratory rate with nostrils flaring, and use of accessory respiratory muscles. They will check for asymmetrical lung expansion, tactile fremitus which will be decreased and find a hyper resonant percussion note. They will also find on auscultation, decreased breath sounds, or absent breath sounds.

In tension pneumothorax, the heart rate increases more than 120 beats per minute, the blood pressure drops, there is distention of the jugular veins, and it could result in respiratory failure and cardiac arrest. In some fighters, subcutaneous emphysema is present. The diagnosis of tension pneumothorax is made by a good physical exam.

Imaging

Chest radiography, ultrasonography, and CT are all used to diagnose air in the pleural space. Commonly, a chest x-ray is more than enough. 2.5 cm of air space is almost a 30% pneumothorax on Chest X-ray. Occult pneumothorax that is too small to be significant is diagnosed by CT. The extended focused abdominal sonography for trauma (E-FAST) exam is used in the trauma bay to diagnose pneumothorax. If a fighters’ vital signs are unstable and blood pressure is dropping fast, for suspected tension pneumothorax, imaging is not needed. Immediate intervention via needle decompression is done.

Lab tests

Blood tests are not needed to diagnose a pneumothorax or hemothorax.

To learn how Pulmonary Injuries is treated Click Here

A thorough physical exam must include cardiac, respiratory, and head and neck exam. Fighters who have jugular venous distention and hypotension must be examined for cardiac tamponade. Initial vital signs are obtained and monitored, after making sure the airway and breathing are intact. A quick evaluation of circulation and the cardiac system is done. The chest wounds are checked, the chest wall is auscultated for any muffled heart tones, murmurs, and arrhythmias. The strength and presence of peripheral pulses are examined.

Any increased respiratory rate, irregular lung sounds, tenderness in the chest wall, chest abrasion or ecchymosis, rib or sternal fractures must be noted and raise suspicion for cardiac injuries.

Plain films of the chest are useful for diagnosing penetrating cardiac trauma. They demonstrate the presence and location of a foreign body if there is a hemothorax, heart displacement, and other thoracic injuries.

POCUS with a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is more diagnostic. It can rapidly diagnose pericardial effusions. Inferior vena cava distension is identified on POCUS. Transesophageal echocardiography can provide additional information about the major vessels if the fighters' vital signs are stable.

CT is also diagnostic for pericardial or myocardial lacerations, cardiac luxation, other thoracic injuries.

ECG is not standard but helpful to identify new dysrhythmias. For myocardial contusion, cardiac magnetic resonance (MRI) can identify the extent of the contusion.

Echocardiography is very specific for cardiac wounds if there is a penetrating injury.

In addition to the complete blood count and basal metabolic panel, cardiac enzymes such as cardiac-specific troponins can identify a myocardial contusion or ischemia secondary to vessel damage.

To learn how Cardiac injuries are treated Click Here

On physical exam, the fighters present differently depending on the location and mechanism of the injury. The diaphragm plays a very important role in normal respiration. So fighters with these injuries present with respiratory distress. The doctors’ physical exam focuses on airway, breathing, and circulation. They will inspect for a mediastinal shift or any displacement of the lungs. The chest is auscultated to check if bowel sounds are heard in the chest. A very high index of suspicion is necessary to diagnose diaphragmatic injuries. Doctors also examine the neck and chest for tracheal deviation, absent breath sounds, or asymmetrical chest expansion. An abdominal exam might also present an empty scaphoid abdomen, with the diaphragm moved to the chest.

A FAST (Focal Assessment with Sonography for Trauma in the trauma bay will show a hyperechoic, curvilinear line above of the liver or the spleen. An upright plain chest X-ray is the best initial study. It does miss up to 50% of the cases. A chest x-ray shows raised hemidiaphragm on the affected side. Any visceral herniation is seen as diffuse and loculated gas bubbles.

A nasogastric tube can be diagnostic. Any coiling of the NG tube into the chest on a plain film of the chest is diagnostic of a diaphragmatic rupture.

CT of the chest and abdomen is more specific. On CT, these injuries are seen as an interruption of the diaphragm, abdominal viscera herniation, constriction of abdominal viscera in the form of a "collar sign", or free-floating diaphragmatic flaps.

A diagnostic laparoscopy under general anesthesia is done where imaging is inconclusive. Thoracoscopy is used to evaluate an ipsilateral hemidiaphragm or a 45⁰ scope can evaluate the entire hemidiaphragm for defects.

The defects are graded from I to V on a scale developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Blood tests are not required to confirm or diagnose diaphragmatic injuries.

To learn how Diaphragmatic injuries are treated Click Here

The physical exam of the neck, chest, and abdomen may not be entirely specific but must be done. The findings of Mackler’s Triad which includes subcutaneous emphysema, chest pain, and vomiting is diagnostic for esophageal perforation. The Hamman sign, where there’s a systolic "crunching" synchronous with the heartbeat is found over the precordium while examining the heart.

The doctors check for cervical esophageal injury symptoms like dysphonia, hoarseness, dysphagia, and subcutaneous emphysema. For thoracic esophageal perforation, they will check for mediastinal or pleural findings like shortness of breath and chest tenderness. Vital signs are monitored to ensure no shock ensues from blood loss or hemodynamic compromise.

Plain radiography detects air escaped from the perforated esophagus. There is mediastinal air (pneumomediastinum), and widening which is diagnostic of thoracic perforation. On Xray, if there is free air under the diaphragm, esophageal perforation is confirmed. Plain X-rays can also detect the presence of pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, hydrothorax, hydropneumothorax, and air in soft tissues of the prevertebral space.

Contrast esophagography confirms the diagnosis of esophageal perforation. Any leakage of contrast material establishes the diagnosis of perforation. Dye extravasation determines the location and extent of the rupture.

Barium contrast studies are better than water contrast studies. However, the latter are preferred since they cause less irritation.

CT scan of the chest and abdomen is done as it shows intrathoracic or intra-abdominal collections that require percutaneous or surgical drainage.

Blood tests are not required to confirm any esophageal tears, rupture, or perforations.

To learn how Esophageal tears are treated Click Here

Common Diagnoses

Learn more about how physicians assess common chest injuries through electrocardiograms, X-rays, and other tests in our Common Diagnoses section.

Chest Injury Treatment

The treatment of chest injuries differs widely based on the organ involved. Chest trauma usually ends up being multi-trauma. However, all treatment of chest injuries starts with the ATLS protocol.

Injury Specific Treatment

Emergency

Fighters with acute sternal fractures are managed with ATLS guidelines. After the airway, breathing, and circulation are evaluated, a primary survey is done to assess any life-threatening injuries such as tension pneumothorax, hemothorax, cardiac tamponade, and flail chest. If these injuries are present, their treatment takes precedence. A secondary survey for rib fractures, pulmonary contusions, and blunt myocardial injury is done.

Medical

Electrocardiography and cardiac monitoring are done for fighters with sternal fractures. Those with intrathoracic injuries, unstable vital signs, uncontrolled pain, are admitted for observation.

Pain management is the mainstay of treatment for isolated sternal fractures. Fighters must see their primary care physician within the first 24 hours after presenting to the trauma bay.

Fractures that are displaced or unstable, require operative fixation.

Home

Deep breathing exercises are advised to all fighters with sternal fractures. This is to avoid pulmonary complications like lung collapse. Most isolated sternal fractures heal spontaneously over 10 weeks.

Emergency

For fighters with signs of instability, needle decompression is the immediate treatment of a pneumothorax. This is done by inserting a 14- to 16-gauge and 4.5 cm in length angiocatheter, above the rib in the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line. After needle decompression, a thoracostomy tube is inserted. This usually is placed in the fifth intercostal space.

Open "sucking" wounds are treated with a three-sided occlusive dressing followed by tube thoracostomy.

Medical

In fighters with no symptoms, small primary spontaneous pneumothorax less than 2cm deep are discharged. After 2-4 weeks, the injury is examined. If the fighter still has no symptoms and the depth is more than 2cm, it is aspirated with a needle aspiration is done. If it improves and there is no more residual air, the fighter is sent home, otherwise, tube thoracostomy is done.

If the pneumothorax on plain films is about 25% or larger it needs treatment with needle aspiration especially if the fighters display symptoms. If aspiration fails, tube thoracostomy is done.

Surgical intervention is done if there is a continuous air leak for more than seven days, those who have pneumothorax in both lungs and for those who have it recurrently.

This procedure is a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) whereby pleurodesis is done to occlude pleural space. In mechanic pleurodesis, the parietal pleura is stripped or scratched using dry gauze. Chemical pleurodesis is done for those who cannot tolerate the mechanical procedure with chemicals like tetracycline or doxycycline.

Home

Pneumothoraces mostly resolve on their own without any major intervention. They have to be carefully monitored. Fighters can return to play in 2-10 weeks. Pain determines return to play. Return to fighting is done only after the radiographic resolution of the pneumothorax. The return must be gradual progression to full activity.

Advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) management is the first step for all should be initiated for dysrhythmias. A beta or calcium channel blocker is given to a fighter with stable vital signs. In the unstable fighter, electrical cardioversion is done.

Treatment for myocardial contusions is supportive and determined by the severity of the injury. Cardiac rupture is fatal and depends on the location and damage to the cardiac tissue. Surgical repair is needed with a sternotomy or thoracotomy, with a cardiopulmonary bypass. Valvular injuries are also repaired or the valve is replaced depending on the type of injury.

Lacerations to the coronary artery are controlled via surgery of the involved artery and coronary bypass. Non-bleeding coronary artery injuries can be stented or treated medically.

Penetrating cardiac trauma requires surgery. If there is a hemopericardium, a pericardiocentesis is done with a catheter placed for intermittent drainage. This is followed by a median sternotomy or thoracotomy. Lacerations are controlled with digital pressure, vascular clamps, or the insertion of a Foley where the balloon is inflated followed by light traction.

Cardiac lacerations are repaired using 3-0 polypropylene (Prolene) sutures. They are done in a running, horizontal mattress, or purse stitch. Pieces of the pericardium are used to distribute tension in ventricular wound repair.

Return to play depends on multiple modifiers. These include the type of injury, the extent of myocardial damage, arrhythmias, preload and afterload capability of the heart, type of treatment, and the nature of arrhythmias. Most fighters can return to training but not fighting pending clearance from the cardiologist. Two to three months after all labs have normalized and the surgical scare fully healed, cardiac rehabilitation is advised, followed by a return to light activity.

In the trauma bay, following ATLS, and FAST, it’s important to transfer the fighter for surgery.

An open laparotomy to reduce any visceral herniation is the next best step. It can also repair the defect. In fighters whose vital signs are stable, laparoscopy is an alternative.

A nasogastric or orogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. The entire abdomen is inspected along with the diaphragm and any herniated visceral contents are reduced. Contamination due to spillage is irrigated with antibiotics-infused normal saline.

After visceral herniation through the diaphragm has occurred the fighter is treated with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or a thoracotomy.

The defect is debrided and repaired with simple, non-absorbable sutures, in interrupted or in a continuous fashion. Larger defects are bridged with a prosthetic mesh. They are secured with interrupted monofilament sutures.

Contaminated defects are temporized with a biologic mesh. It is replaced by a synthetic mesh at a later date.

Watch out for respiratory discomfort that results from damage to the phrenic nerve during surgery. A proper pulmonary toilet has to be done to prevent atelectasis. Pain management is advised. Return to play is advised only after the respiratory effort is normal and the surgical scar completely healed.

Since this injury is fatal with mortality reaching as high as 50%, initial management is important. This includes ICU admission for all fighters with unstable vital signs and those with multiple injuries. The hemodynamic status is monitored. Volume resuscitation and stabilization must be achieved. The fighter is kept NPO (Nil Per Os) with TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition). Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals are started to prevent infections. Intravenous proton pump inhibitors are also initiated. If there is any fluid collection, percutaneous drainage is done along with the insertion of a feeding J-tube.

In stable fighters, endoscopic stent placement is done. Perforations are covered with synthetic stents via esophageal endoscopy. Drainage with or without debridement is also done.

Surgical management is done in fighters diagnosed less than 24 hours after the perforation. They are treated with debridement of contaminated tissue. This is followed by primary repair.

Fighters with extensive leakage of fluid or fluid collections must have emergent surgical stenting, debridement, or drainage.

Rarely, a diversion procedure or resection of the esophagus with proximal esophagostomy and feeding gastrostomy/jejunostomy is done for fighters with extensive contamination.

After the surgery, healing is better if the fighter refrains from oral feeding. A feeding jejunostomy or gastrostomy tube is placed for the esophagus to heal. This is especially if there was a substantial extraluminal leakage.

Oral diet is resumed when the fighter’s vital signs have stabilized and a contrast esophagogram study confirms the integrity of the esophagus. It must also confirm that leakage has completely stopped.

Common Treatments

Read more about how chest injuries are treated in a variety of ways in our Common Treatment section.